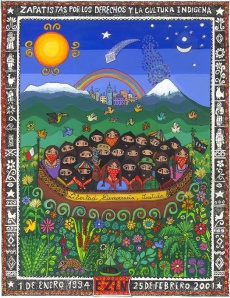

“Esta pirâmide absurda e invertida que é a América Latina…” – Uma jornada com o Subcomandante Marcos (EZLN)

CHAPTER III – THE CLASH BETWEEN OBLIVION AND MEMORY

“…there once was a man named Zapata who rose up with his people and sang out: ‘Land and Freedom!’ The campesinos say that Zapata didn’t die, that he must return… They say that hope is also planted and harvested. They also say that the wind and the rain and the sun are now saying something different: that with so much poverty, the time has come to harvest rebellion instead of death.” – Sub Marcos, Our Word is Our Weapon

: Selected Writings, pg. 33, Seven Stories Press. All following quotes are from this source.

The Zapatistas know their task is Herculean: the Mexican federal Army, certainly backed-up by Washington and Wall Street, greatly outnumbers the army of the Zapatista rebels. The power of destruction of the Establish Capitalist Powers is crushing: they own the police and the prisons, and they pay the soldiers and militias to persecute the Mexicans who join EZLN. The defeat of this insurrectional movement is something that has been aimed at by established powers for the last 20 years – according to Marcos, the enemy would like to see “democracy washed with the detergent of imports and water from antidemonstration cannons.” (pg. 54)

The Zapatistas know their task is Herculean: the Mexican federal Army, certainly backed-up by Washington and Wall Street, greatly outnumbers the army of the Zapatista rebels. The power of destruction of the Establish Capitalist Powers is crushing: they own the police and the prisons, and they pay the soldiers and militias to persecute the Mexicans who join EZLN. The defeat of this insurrectional movement is something that has been aimed at by established powers for the last 20 years – according to Marcos, the enemy would like to see “democracy washed with the detergent of imports and water from antidemonstration cannons.” (pg. 54)

In 1994 Mexico’s president Carlos Salinas de Gortari is considered by EZLN as “the sales manager of a gigantic business: Mexico, Inc.” (pg. 63) Free Trade, for the Zapatistas, is nothing but capitalism’s “law of the jungle”, and it generates a couple of millionaires while throwing millions into hunger, sickness and death. To use Occuppy Movement’s imagery, the top of the social pyramid, the richest 1% of the country, don’t give a fig about defending the rights of the Mexican people as a whole (the 99%): “the only country mentioned with sincerity on that increasingly narrow top floor is the country called money.” (pg. 63) “On every street corner misery knocks on the windows of the car.” (pg. 64)

Even tough they see peace and social justice as an ideal to accomplish, the Zapatistas feel they would remain powerless if they were Gandhian pacifists. Thus they take arms, just like the guerrillas led by Fidel and Che in Sierra Maestra in late 1950’s Cuba. EZLN, as the name itself sufficiently states, is an armed rebellion and doesn’t comply with what Marcos called, in Aguascalientes, august 1994, “pacifist complicity with injustice” (p. 56) and “fraudulent unconditional pacifism” (p. 58)

EZLN is quite aware that military victory is rather unlikely against such a powerful army as that of Mexico’s established powers, backed-up by Washington and Wall Street. So Marcos tends to underline the symbolical importance of the Zapatista’s up-rising, its capacity to inspire similar movements throughout Latin America. The 4th Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, January 1996, states: “Brothers and sisters of other races and languages, of other colors, but with the same heart, now protect our light, and in it they drink of the same fire.” (p. 87)

“To confront an army superior to ours in weapons and personnel, although not in morality, nullifies the possibilities of sucess. But to surrender has been expressly forbidden; any Zapatista leaders who opt to surrender will be decommissioned. No matter the outcome of this war, sooner or later this sacrifice – which today appears useless and sterile to many – will be compensated by the lightning that will illuminate other lands. For sure, the light will reach deep into the South, shimmer in the Mar de Plata, in the Andes, in Paraguay, and the entirety of this inverted and absurd pyramid that is Latin America…” (74)

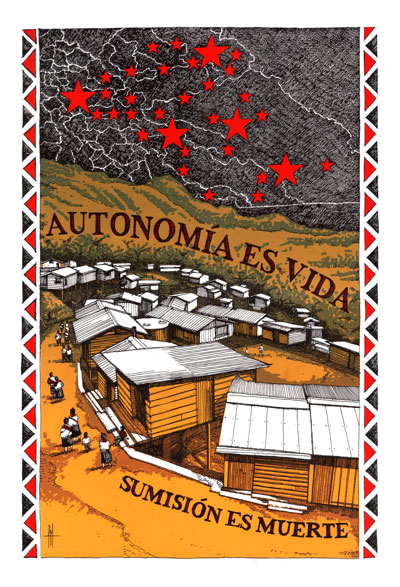

The future of Latin America lies not only in its ability to build international solidarity, planting the seeds of a future of social justice and true democracy, but also in its struggle against oblivion. The Zapatistas claim that memory has been progressively wipe-out by the forces of a capitalist production, distribution and consumption system that runs on shallow foresight and narrow hindsight. In other worlds: the system wants us to buy like crazy, and think only of immediate enjoyment of products sold in the markets, thus imposing to our minds oblivion of future and past generations. This is one of the most important ideas to understand if we want to grasp what these more than 20 years of the Neo Zapatista movement in Mexico means:

“On the side of oblivion are the multiple forces of the market. On the side of memory is history.” This thesis of the markets’ attempted murder against memory is illustrated by the treatment conferred upon indigenous populations by capitalists and their accomplices among politicians. The Zapatistas are saying: the past is not to be forgotten, consumed down to ash, thrown in the garbage can, in order for us to “enjoy” the here-and-now of mass society, mass production, mass consumption, and mass ecological catastrophes. The Zapatistas see the past as “a guide to be learned from and upon which to grow”. The problem is:

“the past doesn’t exist for technocrats, under whose rule our nation suffers. The future can be nothing more than a lengthening of the present for these professional amnesiacs. (…) What better example of this phobia of history is there than the attitude of the Mexican government toward the indigenous peoples? Are not the indigenous demands a worrisome stain on history, dimming the splendor of globalization? Is not the very existence of indigenous people an affront to the global dictatorship of the market?” (MARCOS, pg. 147)

The sad thing is: instead of learning from the past in order to build a better future, the authorities in charge of markets and governments complicit to them are basically waging war against those who are labeled by the repression forces and portrayed by the plutocratic media as “The Terrorists”. The inner enemy. The war against the Zapatistas waged by the Mexican Federal Army, with the aid of the Yankees, is simply an attempt to silence by massmurder those who are demanding freedom, dignity, and social justice. In March, 1995, EZLN writes “to the people of Mexico and to the peoples of the world”:

“Our voice was silenced all at once by the noise of the machines of war. Terror was unleashed again in the Mexican lands by the one who, from arrogance and power, looks at us with contempt, denies our name, and gives us death in answer to our thought. (…) With the complicity of big money and a foreign vacation, he wanted to force us with bayonets to deny our history. (…) For that reason, our past went to the mountains. We went into the caves of those who came before us. Death cornered us… Death came to wield its knife-edged oblivion. It came to kill memory. Again, our hand filled with the fire to avenge our own pain, again being animals eating dirt, dying persecuted and forgotten.” (pg. 81)

The name Zapatistas then gains the meaning of a very powerful symbolical weapon: a “collective name”, that any individual can claim for himself, and by adhering to it he goes away from the forgetfullness that his individual self lies buried in. A campesino who haves always felt as nobody, as one of the many who History will forget, now can call himself a Zapatista and thus believe he’s part of a collective entity that won’t be so easily brushed away to oblivion. Every zapatista will die, but zapatismo will live, beyond the duration of individual lives. When an individual leaps from being an unrelated isolated atom and joins his forces with the supra-individual movement, it’s as if his heart has been connected to a vaster entity and now pulsates with a collective heart.

“No longer are we the unmentionables. We the forgotten have a name. (…) Having now a collective name, we discovered that death shrinks and becomes small before us. The worst death, that of oblivion, flees so that the memory of our dead will never be buried together with their bones.(…) “They, our ancestors, taught us to be proud of the color of our skin, of our language, of our culture. More than 500 years of exploitation and persecution have not been able to exterminate us. (…) If they destroy us, the entire country will plummet and begin to wander without direction or roots… Mexico would negate its tomorrow by denying its yesterday.” (October 12, 1995, pg. 82-83)

* * * * *

You might also enjoy:

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/cNR-uv34g2o]

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/gQp7zNWMVAg]

TO BE CONTINUED…

Copyleft material. Re-share and re-blog as much as you wish,

but please acknowledge Eduardo Carli de Moraes @ Awestruck Wanderer.

Publicado em: 28/03/14

De autoria: casadevidro247